Clandestine Classes, Classified Homework, and Oaths of Secrecy: Wellesley’s WWII Code Breakers

On a brisk November afternoon over 75 years ago, Ann White Kurtz ’42, then a Wellesley senior, returned to her dormitory after attending a lecture on Spanish romanticism to find a curious letter in her campus mailbox. A German major, Kurtz was surprised to see it was from Helen Dodson, professor of astronomy, inviting her to a private interview in the observatory. Dodson asked her two questions: Did she like crossword puzzles, and was she engaged to be married?

Kurtz, along with classmates Nan Westcott Day, a botany major, Spanish major Blanche DePuy, English major Louise Wilde O’Flaherty, and several others, answered yes to the first question, no to the latter. Selected for their high academic achievement, personal character, and grit, these seniors became the first cohort of Wellesley students to be recruited to serve their country on a crucial, top-secret wartime mission: cryptanalysis, or code breaking.

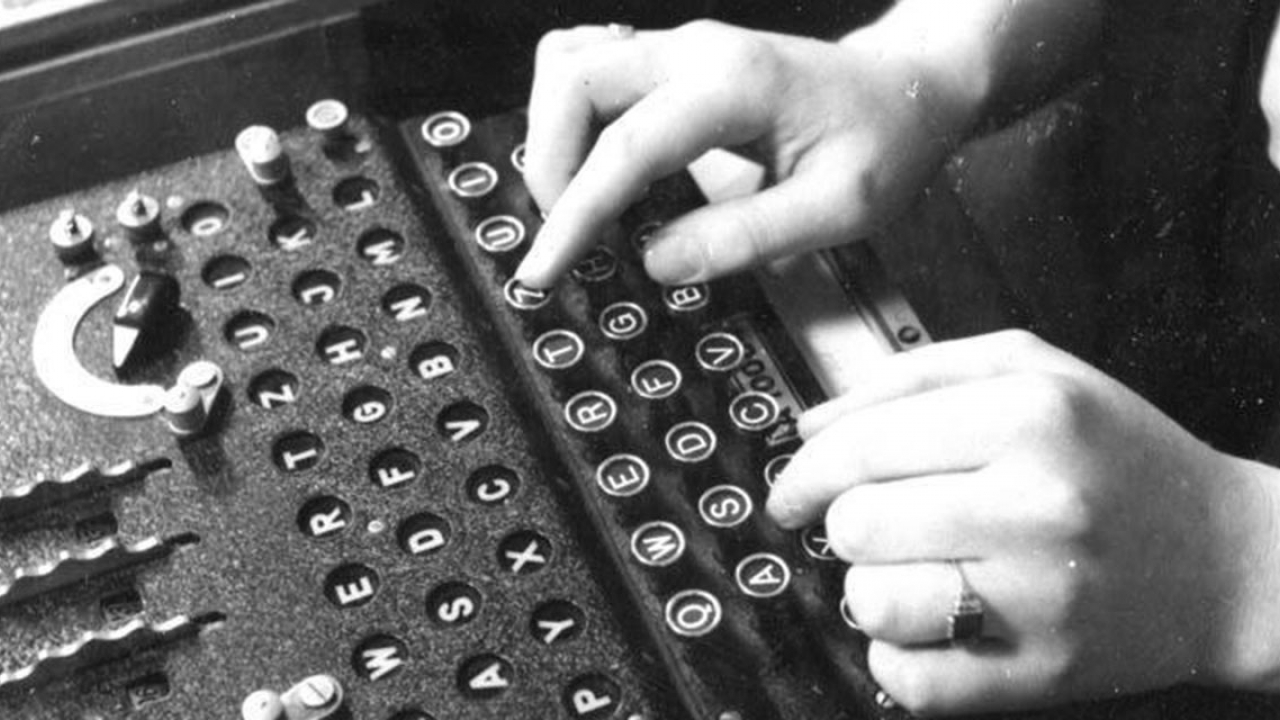

Their clandestine training began with a U.S. Navy correspondence course overseen by Dodson and Barbara McCarthy, professor of Greek. Held once a week in the observatory, where lights on late would not arouse suspicion, the course introduced the history and fundamentals of cryptanalysis. The students learned about the mathematical properties of language, the frequency of individual letters and letter combinations, various cipher alphabets, and the Vigenère square, a method of disguising letters dating from the Renaissance. They received numbered problem sets in manila envelopes to turn in to the navy—homework assignments that had to be carefully concealed under desk blotters and quilts.

Those who passed the course were sent to Washington to begin their work with the newly established WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), a division of the U.S. Naval Reserve. WAVES was led by Mildred McAfee, then president of Wellesley, who took a leave of absence from the College to serve as the unit’s first director; she went on to become the first commissioned female officer in the U.S. Navy, ultimately reaching the rank of captain, before resuming her duties at Wellesley in 1945.

The code breakers of 1942, as they were called in a 2000 Wellesley magazine article, joined women recruited from fellow Seven Sisters schools and other women’s colleges across the nation, as well as college-educated former schoolteachers from all over the U.S, to embark on the monumental task of starting a wartime intelligence operation from scratch—a task made all the more urgent after the attack on Pearl Harbor. In all, about 21 Wellesley students from the class of ’42 and many more from the classes of ’43 and ’44 were summoned. They worked in teams, deciphering coded Japanese and German messages 24 hours a day in three eight-hour shifts. Kurtz, who was assigned to decipher and translate German messages to and from U-boats, remembers learning about D-Day, which she experienced from the perspective of the Germans: “I was on midnight watch with a gorgeous full moon and thought, ‘No invasion tonight.’ Then the traffic started coming in with the numbers of ships, etc. The next day we read about the landings in English, but in our minds D-Day remained in German.”

Over the course of the war, code breakers were instrumental in disrupting enemy operations, saving thousands of Allied lives and shortening the war by as much as a year. Women code breakers, who numbered around 11,000, comprising the majority of cryptology personnel, were behind some of the most significant intelligence coups of the war, including the identification of the plane carrying Japanese Admiral Isokuru Yamamoto, which enabled the U.S. to shoot down Japan’s chief naval strategist.

The work of the code breakers also left a rich legacy: It formed the backbone of what is now known as signals intelligence and laid the groundwork for the new field of cybersecurity, and the combined U.S. Army and Navy code breaking operations became the NSA. Yet, despite the vital contributions of code breakers, they have received little official recognition. The few public comments by military and government leaders praising code breaking efforts do not mention women at all. Sworn to secrecy under pain of death, and with their files classified until the late 1960s, few have come forward, and only a handful of books have been written on the subject.

Like other unsung heroines of World War II, Wellesley’s code breakers took diverse paths after the war. Many embraced domestic life, getting married and raising children; others attended graduate school on the G.I. bill, and went on to other professional careers; still others stayed in Washington, helping to shape the direction and culture of the NSA. They remained silent on the subject of code breaking for over 30 years.

Kurtz, who noted she was told she would be shot if any leaks were traced to her, reflected 55 years later, “Never in my life since have I felt as challenged as during that period. Like Hegel’s idea about when the needs of society and the needs of an individual come together, we were fulfilled.” With legions of men fighting on the front, World War II offered rare professional and educational opportunities for women, even if on a somewhat limited and temporary basis. In addition to code breaking, over 200 Wellesley women joined WAVES, taking the unique opportunity to serve their country while expanding the notion of what it was possible for women to achieve.

Photo: Americans like Wellesley's Code Breakers used the Enigma machine (pictured) to decode German signals during World War II.