From the moment she entered Yankee Stadium as a recently hired sports reporter in the early 1970s, Melissa Ludtke ’73 knew she stood out. She could feel the stares of the other reporters—all men—as she joined them on the field, and she knew right away that she would have to fight to stand on the ground they took for granted.

Fifty years later, Ludtke returned to Wellesley College to share her experiences as a sports journalist in conversation with Geneva Overholser ’70, a fellow veteran reporter. Overholser gained recognition in 1989 as an editor of the Des Moines Register after she published the name and photo of a rape victim, which was not standard practice at the time. At the September 23 event, co-sponsored by Wellesley’s Department of Women’s and Gender Studies and Physical Education, Recreation, and Athletics, they talked about their experiences as pioneering female journalists and how the field has changed during their careers.

Ludtke’s career was shaped by her groundbreaking 1978 lawsuit against Major League Baseball, Ludtke vs. Kuhn. She chronicles her time at Sports Illustrated and the suit in her 2024 book, Locker Room Talk: A Woman’s Struggle to Get Inside. At the event, Ludtke said she joined Sports Illustrated as an entry-level reporter shortly after graduating from Wellesley with a degree in art history, an opportunity that “just magically came together.” Her supervisor assigned her the baseball beat, which thrilled Ludtke, an avid fan of the sport from a young age thanks to her mother.

Ludtke soon found that a major barrier stood between her and her work: misogyny. The men on the field—players, reporters, and executives—felt she was invading their boys club. “When a few women dared to show up in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s … they weren’t allowed on the field during batting practice, they were not allowed to sit in the press box with the men,” she said. “They were not allowed to eat their meals with the male sports writers.” Ludtke paused, then asked the audience to consider whether any of those events involved nudity.

Ludtke was referring to the fact that Major League Baseball’s reasoning for not allowing female sports writers into the players’ spaces rested on the idea that if the women witnessed undressed or partly dressed players, they would be morally corrupted or inappropriately titillated. “It was never about nudity … [MLB] wanted to turn it into a morality play that would play into the culture,” said Ludtke. “This was about excluding women.” Backed by Sports Illustrated, she sued. The court determined that MLB’s policy violated Ludtke’s 14th Amendment rights, thus transforming the world of sports journalism.

Overholser spoke about the effect her editorial decision to print rape victim Nancy Ziegenmeyer’s name and picture, per Ziegenmeyer’s request, had on her personally and professionally. She recalled the Des Moines police department blocking her from accessing files to rape cases, and being threatened by one of its officers. Since then, Overholser has written and edited a number of articles on rape coverage by the media, and she remains a key figure in the national discussion.

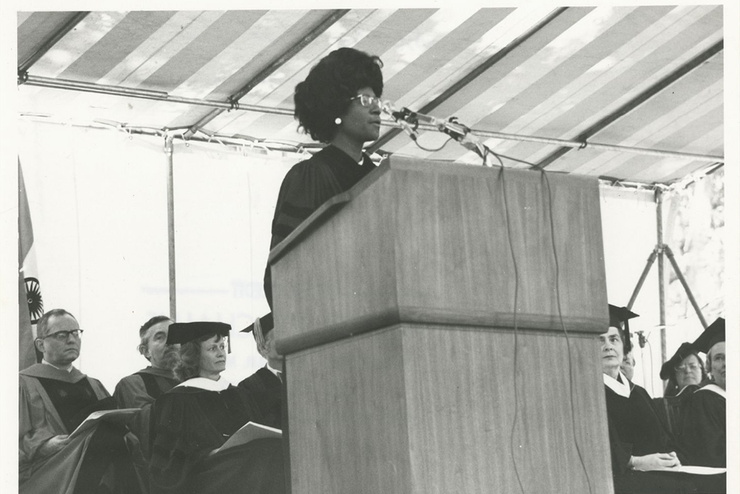

While both women were frank about the challenges they faced in their careers, they also discussed their passion for the work and the excitement they felt as young journalists. It was Wellesley that sparked that excitement. Ludtke recalled listening to Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress and the first Black candidate to seek the nomination for president under a major party, deliver the 1973 commencement speech, and the impact Chisholm’s message had on her. She told the graduates to go out into the world and “be part of the movements of our time, the Civil Rights movement, the women’s movement,” Ludtke remembered. “She lit a fire under me.”

Overholser discussed the Wellesley environment’s influence not only on her career aspirations, but on how she saw herself as a woman in the world. “Everybody here makes you feel that women can be everything. Women can be jocks, they can be brainiacs, they can be nerds,” she said. “Everything about this place made me think I could do whatever I wanted to do.”

Ludtke said Wellesley taught her to take leaps of faith. “There were certain junctures in my life where opportunities were presented that I could have perhaps looked past,” she said. “Even if it was a huge challenge, if I didn’t have any concept of what the path was ahead, I took it, and that made all the difference—just having the courage to take that path.”

After the discussion, students and faculty reflected on the wisdom of these two inspirational women and how they could apply it in their own lives. Bella Gilmartin ’25 spoke about the importance of hearing how the previous generations of Wellesley women “opened the doors that we take for granted.”

“Just to know that it was our predecessors here who were making those cases, going to court for this, having to stand out and be exceptional—it feels good, [knowing] that’s the legacy we’re stepping into,” she said. The event reinforced for her the significance of Wellesley’s mission to “put people out there who are going to continue to make progress.”

Grace Kessler ’25 said Ludtke and Overholser’s stories reminded her that it is vital to keep showing up, no matter the odds. “I work in very male-dominated spaces … and I get so frustrated by it sometimes,” said Kessler, who is working toward a career as an EMT.

But learning about the difficult path Ludtke and Overholser faced allowed her to put her experiences in a larger context. She said she realized that although the spaces she puts herself in might not seem welcoming now, she should stick with it to make change for future generations of women. Like Gilmartin, Kessler’s major takeaway from this conversation was Wellesley’s key role in shaping trailblazers: “This really is a place where you can do anything.”